K-Value Justification: Distinguishing Semantic from Syntactic Joins

Link to notebook. The notebook includes all the necessary code to create the data that we need and generate the plots. Nonetheless, an iteration of this data is already contained here, under the k_justification folder.

Theoretical justification

Conceptual intuition

We first provide a conceptual intuition on the hypothesis we pose in the paper: “two sets of values with widely different cardinalities represent different semantic concepts”. For that, we can point to the philosophical concept of Natural Kinds. This principle posits that the world is not an unstructured collection of objects, but contains real categories and groupings (e.g. chemical elements or biological species) that exist independently of human classification schemes. These are not arbitrary sets; they are structured components of reality.

Drawing from the concept of Natural Kinds (i.e., the idea that certain categories exist in reality with intrinsic properties) our hypothesis is that semantically distinct concepts often have an inherent and characteristic domain size. For instance, a column representing UN-recognized countries will naturally have a cardinality around 195, while one for U.S. states will be close to 50. In a data lake, where datasets are created independently, different columns representing the same underlying concept will almost certainly have similar cardinalities. For instance, a column with 50 distinct values is a plausible candidate for representing ’U.S. States,’ but a column with over 7,000 is not. The column’s cardinality thus acts as a powerful, lightweight statistical signature for the semantic concept it represents. A large discrepancy is therefore a strong, lightweight statistical signal of a semantic mismatch.

Theoretical motivation

We provide an information-theoretic justification for why cardinality proportion serves as a proxy for semantic relatedness in data lakes. For that we adopt notions from information theory. A column of data can be viewed as a random variable, and its information content, or uncertainty, can be quantified by Shannon entropy. For a column A with |A| distinct values, the maximum possible entropy (which occurs when all values are equally likely, a reasonable baseline assumption in the absence of detailed distributional information) is given by the formula: Hmax(A) = log2(|A|)

This equation reveals a direct, monotonic relationship between the cardinality of a column and its maximum information content. A column with a higher cardinality has the capacity to encode more information. If two columns, A and B, from different datasets are semantically equivalent, they are essentially different representations of the same underlying set of real-world entities or concepts. Then, their capacity to encode information should be nearly identical. This implies that their maximum entropies, Hmax(A) and Hmax(B), should be very close, which in turn means their cardinalities, |A| and |B|, must also be very close. Conversely, a large discrepancy in cardinality implies a large discrepancy in information content. If |A| ≫ |B|, it follows that Hmax(A) ≫ Hmax(B). It is, hence, information-theoretically improbable that two concepts with vastly different levels of complexity, granularity, or scope could be semantically equivalent.

Example 3 on the paper, comparing countries and languages, illustrates this idea. The set of recognized countries is a domain with a cardinality of approximately 200. The set of known languages has a cardinality exceeding 7,000. The respective maximum entropies are Hmax(countries) = log2(200) ≈ 7.64 bits, while Hmmax(languages) = log2(7000) ≈ 12.77 bits. The significant difference in the information content required to represent a member of each set is a strong signal that they are not semantically equivalent. Important remark. This argument justifies K as a filter for obvious semantic mismatches (|A| ≫ |B|) rather than as a standalone semantic similarity measure. Semantically related concepts can have different cardinalities, which is why we combine K with multiset Jaccard in our final metric (Section IV).

Empirical validation

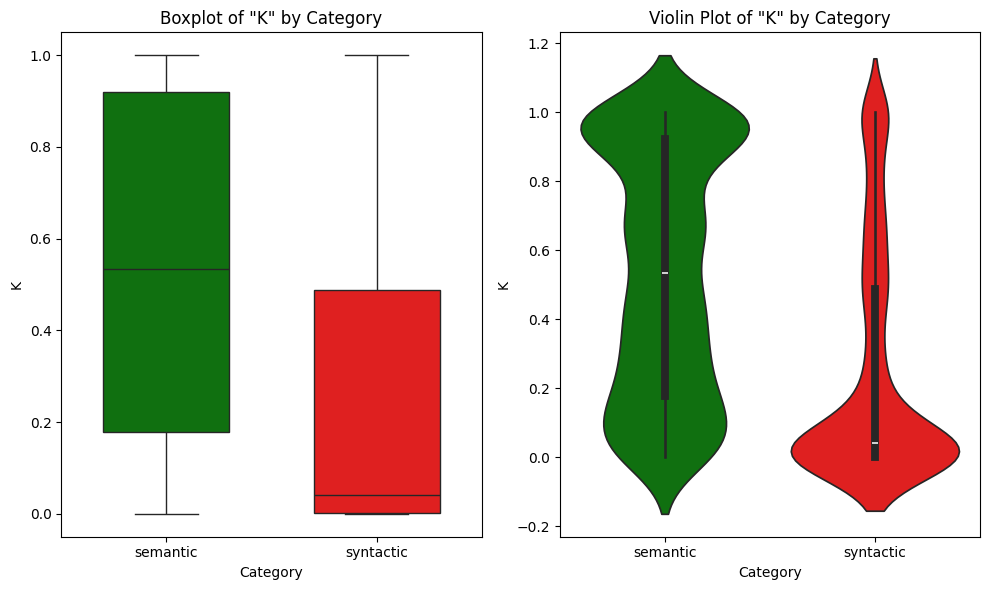

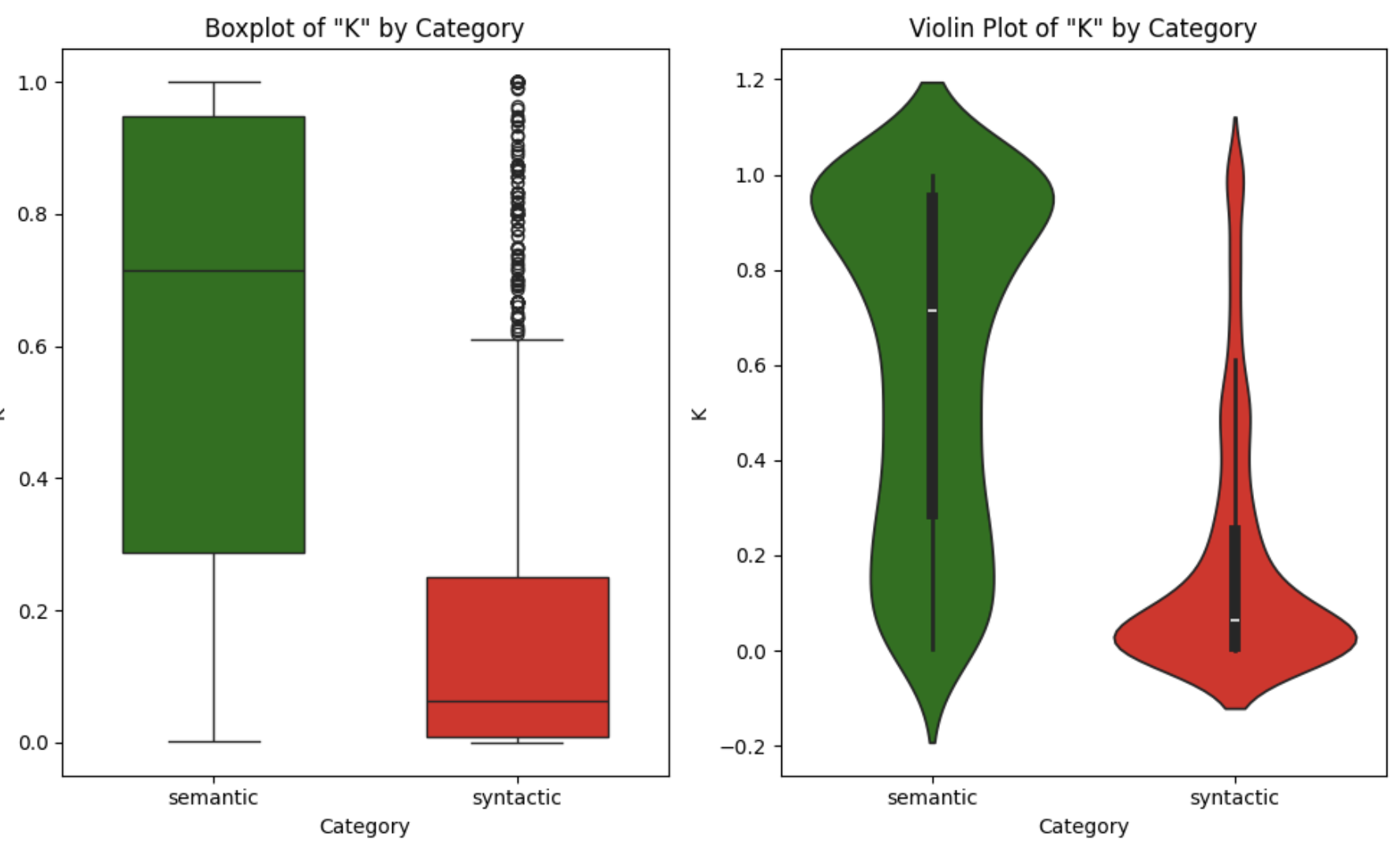

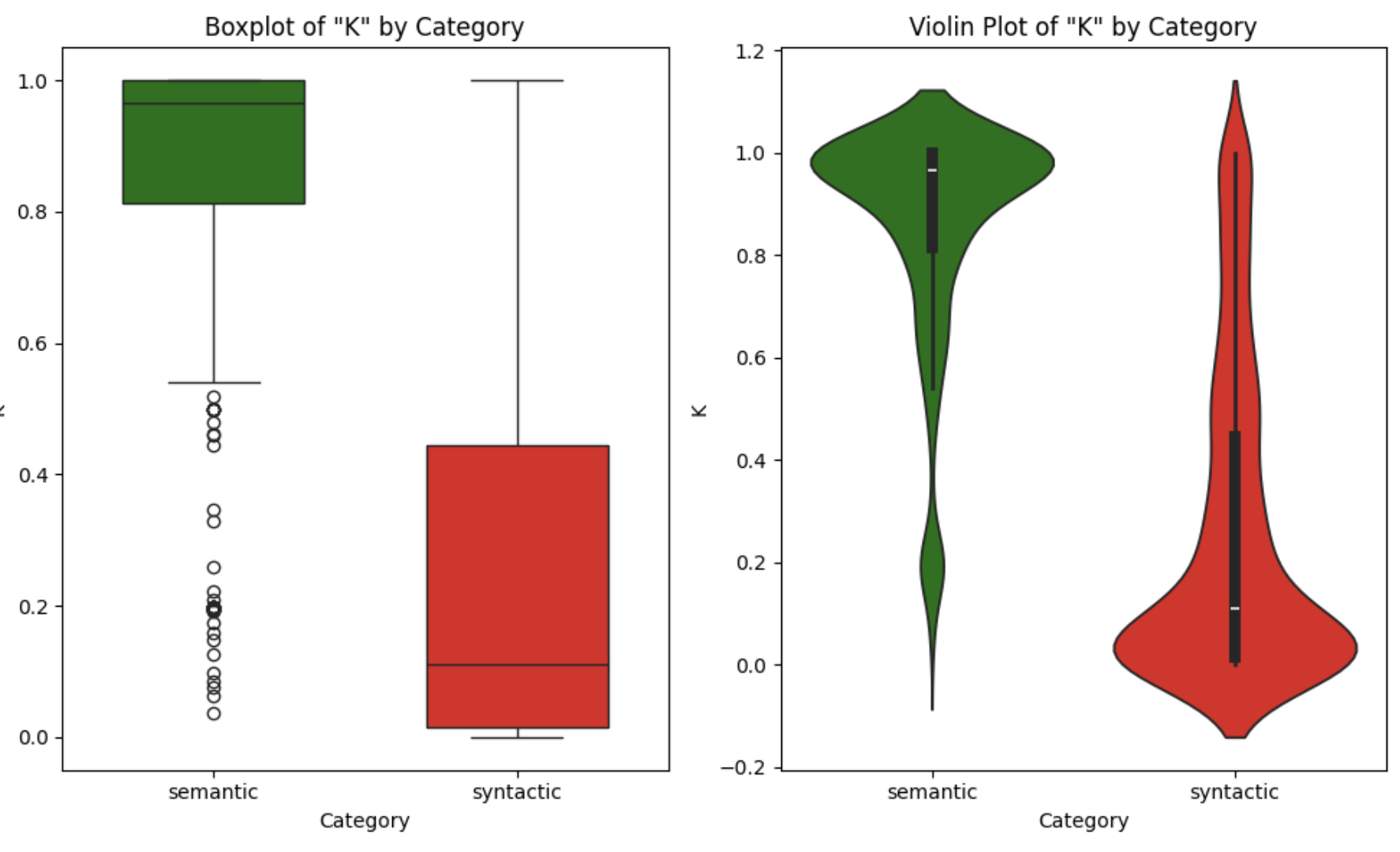

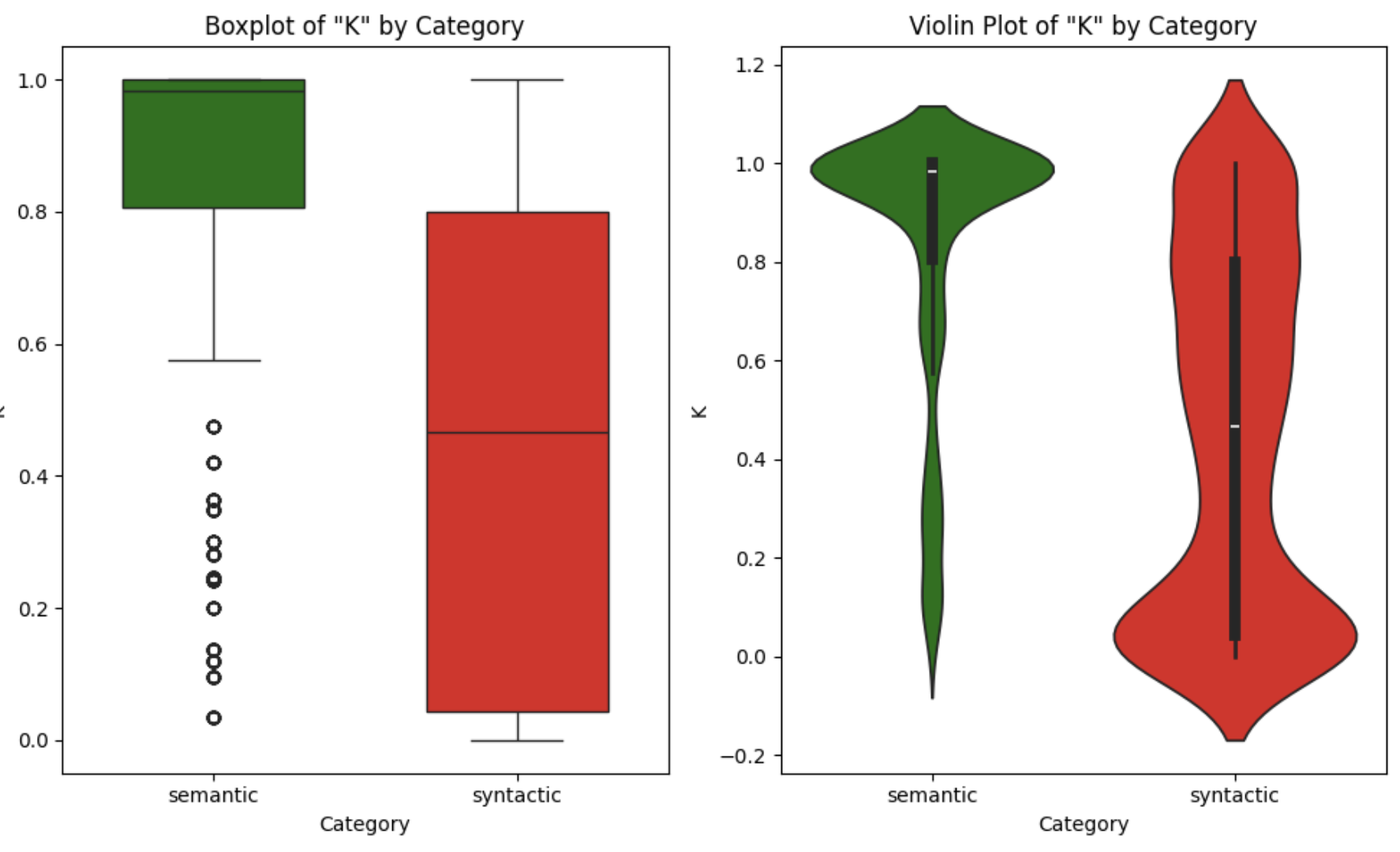

This experiment aims to highlight the relevance of (K) by exploring its capacity to separate semantic joins from syntactic joins across various benchmarks, including D3L, Santos Small, and TUS Small. Since these benchmarks do not provide explicit semantic/syntactic labels, we constructed the evaluation sets as follows: For semantic joins, we sampled 2,000 ground-truth matches (i.e. pairs of query and candidate columns resulting in sensible joins), assuming they share semantic relatedness. For syntactic joins, we sampled 2,000 random column pairs from the data lake with containment > 0.3, matching the criteria employed in the Freyja benchmark.

It is evident that semantic joins generally exhibit higher (K) values. Conversely, syntactic joins display very low (K) values, with the median close to K = 0. This aligns precisely with our design goal for K: to act as a high-level filtering tool that complements traditional intersection metrics and provides a more nuanced assessment of joinability, strengthening the hypothesis that the cardinality proportion can be employed as a lightweight semantic notion regardless of the underlying datalake.

The specific results are depicted below.

Figure 1. Boxplot and Violin plot for \(K\) distribution on the Freyja benchmark

Figure 2. Boxplot and Violin plot for \(K\) distribution on the D3L benchmark

Figure 3. Boxplot and Violin plot for \(K\) distribution on the SANTOS Small benchmark

Figure 4. Boxplot and Violin plot for \(K\) distribution on the TUS Small benchmark

Importantly, both our benchmark (Freyja's) and D3L's are non-synthetic, while Santos Small and TUS Small are synthetic. The distribution of K values varies across benchmarks, but there is always a clear distinction: across non-synthetic datasets, D3L results closely mirror the patterns observed in Freyja, where semantic joins tend to concentrate at higher K values. The same trend holds for synthetic benchmarks, though the distributions are more spread. For instance, in TUS Small, while syntactic joins are more evenly distributed, over 50% of semantic joins have K > 0.98. Conversely, in D3L, 75% of syntactic joins have K < 0.25. In all four datasets, the distinction between semantic and syntactic joins in terms of K is clear, reinforcing our earlier hypothesis.

Please note that K alone is insufficient for join quality assessment, as evidenced by overlap in the distributions (e.g., 15-20% of syntactic joins in TUS Small have K > 0.7). This motivates our combined metric Q(A, B) that uses K as a complementary constraint to multiset Jaccard rather than as a standalone measure.

last updated: 2026/01/07